It’s here! bit.ly/GettingUXDone.

I’m currently at UXLibs 7, so this is good timing. My colleague Paul Harding and I presented at the last User Experience in Libraries conference, in 2022, and then wrote the paper up as a chapter in the 2023 UXLibs Yearbook, which I’d highly recommend you buy for your library… The link at the top of the page is to an Open Access copy of our chapter in the White Rose repository, and you can see lots of other OA stuff (including previous UXLibs year book pieces) on my Publications page.

Ask not what your organisation can do for UX; ask what UX can do for your organisation.

The title of the chapter refers to our central thesis, that we need to spend less time talking about the concept of UX in our organisations, and more time focusing on the results. Sell by doing. Save the library money and give UX the credit afterwards…

We have lots of tips in there about how to truly embed UX, and a case study about the YorSearch Improvement Project, a UX-led piece of work to usher in the new UI for our catalogue. That particular piece of work had a fairly profound ongoing effect on the way we approach User Experience at York, and the ‘three rounds of five’ approach to the fieldwork (detailed in the article) is one we use all the time, including in the recent Website Improvement Project.

Anyway, have a read of the article and let me know if you have questions or would like to discuss any of it in more detail.

A structured introduction to UX in libraries is a whole page of this website, recently revamped, and it displays posts about UX work we’ve done at York. It also features a new quote from Andy Priestner (UXLibs founder and chair) about what UX really is:

“At their core, UX methods are all about making sure that the user is at the centre of what you do. They are about accepting that library services should not be built around staff agendas, convenience, assumptions or gut feelings, but instead around what your users really need and really do. This naturally requires that you regularly connect with, empathise with, involve, and understand your users.

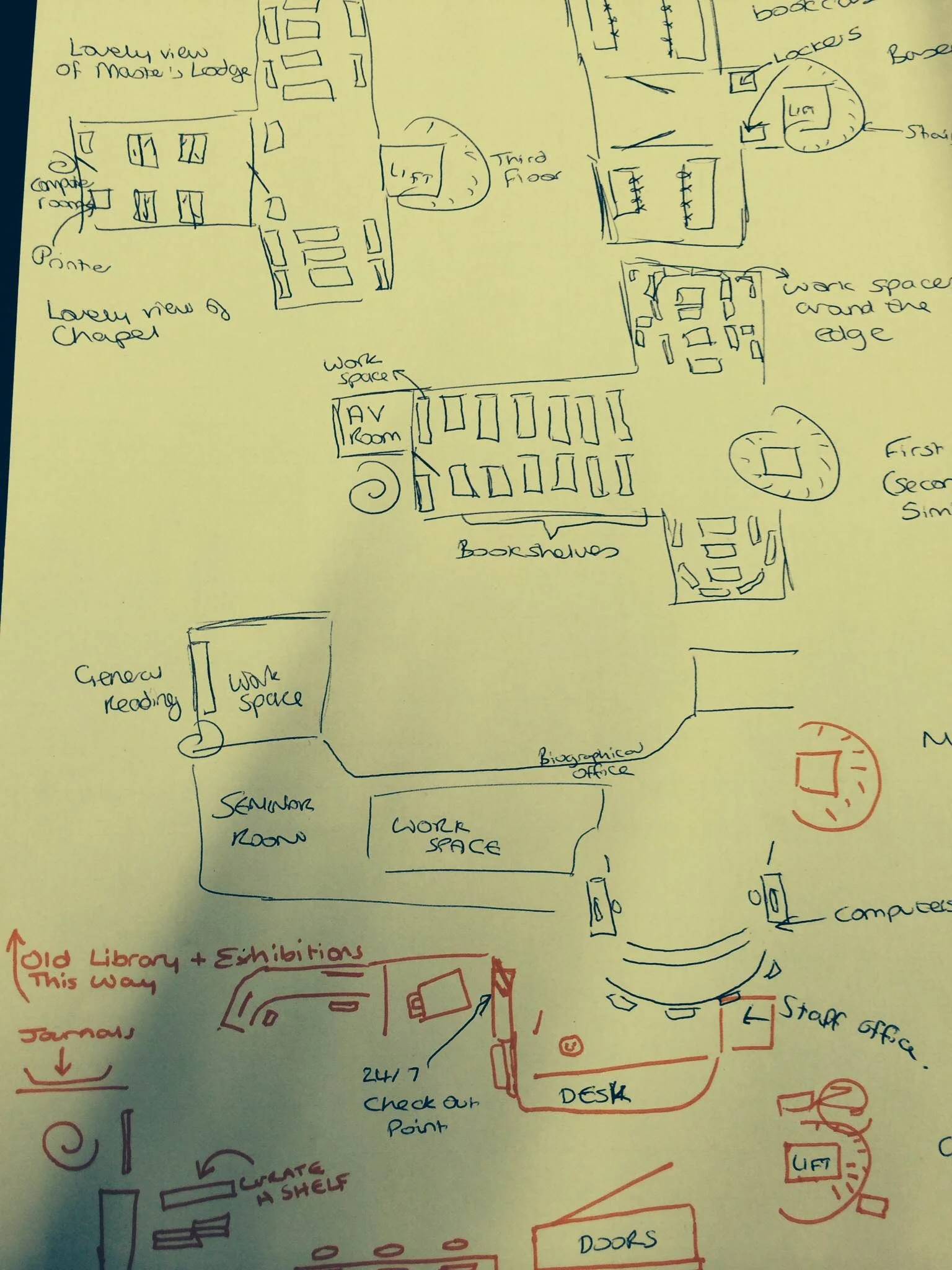

A myriad of UX research techniques are available to explore user activities and needs: attitudinal techniques such as semi-structured interviews, cognitive mapping and photo studies; and behavioural techniques such as observation, behavioural mapping and usability testing. These approaches should always be conducted in balance so you are researching both what people say they do and think they need (attitudinal), and what they actually do and really need (behavioural).

The UX Process begins with user research, continues with data analysis and concludes with the ideation and testing of prototypes. The end result should be investment in more valuable and relevant user-centred services and initiatives, which have been generated from, and tested with, your users.”